Leon Morris: «To enjoy the music and follow your instincts»

An interview with jazz photographer

Leon Morris / photo courtesy of ©Michael Weintrob

Leon Morris is a multi-award winning music photographer. His works was represented by leading London libraries, the Hulton Collection (photojournalism) and Redferns (music), both purchased by famous photo agency «Getty Images». Arriving in the early 1980s in the UK, he began work as the social journalist. From 1982 to 1994, he quickly was building up a high profile photography career working for «The Guardian», «The Observer», BBC Television, The Victoria and Albert Museum′s first photographer-in-residence. In the mid-1990s, Leon Morris returned to his home in Australia, where he completely immersed in his old hobby — music. More than thirty years he is looking for and creates images of musical heroes, twenty of which the muse of master is New Orleans jazz festival (Jazz and Heritage Festival). At the time, Morris captured such legends as Nina Simone, Miles Davis, James Brown, Philip Glass.

In an interview for Orloff Magazine Leon Morris talks about improvisation and the soul of the photograph, and also shares exclusive excerpts from his big project — a book about the musical culture of New Orleans.

Why did you choose the way of music photographer? Who inspired you?

Originally I was inspired by the early committed photojournalistic work of photographers like Margaret Bourke White, Walker Evans and Robert Frank; but I was also strongly influenced by the decisive moment of Cartier-Bresson and the humor and juxtapositions of Elliott Erwitt. My early career was social documentary — I first made my name with a body of work on the black community in west London in the 1980’s. While I was shooting photo essays, stories and portraits for a variety of UK magazines and newspapers during the day, I photographed musicians at night concerts all over London. As the nature of the media industry changed, and the opportunity to publish documentary photo essays reduced, I increased my focus on music photography. The photographer whose work I most admire is Herman Leonard — he wrote the book on jazz iconography and his mastery of technique and composition is second to none. The photographer I most enjoyed working with was my good friend David Redfern, the doyen of music photography in Europe.

David was always very generous in using his contacts and considerable reputation to open doors for me which would otherwise have been firmly shut. It was David who first introduced me to New Orleans, arranging introductions to the festival organizers, concert promoters and a range of key industry insiders and musicians. David and I worked differently. My journalistic background complemented his approach to stage and studio portraiture, and we always enjoyed each other’s company. For twenty years we visited New Orleans together as friends and colleagues: New Orleans was both our workplace and playground for two weeks each year.

I have been known to push the parameters of good sense in the interest of an adventure or an experience, and David was a willing, if more cautions, partner in these adventures. He came to my rescue on at least one occasion — getting me out of a sleazy bar one evening on the outskirts of Clarksdale Mississippi before the lunatic behind the bar could pull out what we assumed to be a gun. The payoff is that we have both experienced much more than we would if we had travelled solo.

Doc Paulin. New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. New Orleans, 1994 / photo by ©Leon Morris

In jazz, one of the key pieces of music is improvisation. Jazz images — is the work of the notes or the creative impulse?

Jazz is in my view a creative language of its own capable of transcending any artificial or imposed boundaries relating to written and improvised music. At its best, jazz is an attitude and a feeling. Great jazz creates room for a conversation between musicians and the audience — it should be as much about the interaction with the audience as it is with other musicians. Great jazz can be defined by the ability of the musician to use silence and space effectively: if there is no room to listen, then the music is noise, not art.

By extension, jazz photography needs to be alive to the possibilities of the moment. It requires technique — you can’t record anything without the right technique — but it also requires you to be aware of the music, the artists and the audience. At some point it kicks over from being pure craft to something that relies on intuition and feel: you have to trust your feelings, enjoy the music and follow your instincts.

Once you said, it has taken you many years to learn to listen to the language of music, particularly jazz. What do you think distinguishes the language of musical photograph?

Great music photography has at its core the desire to capture a fraction of a second that will stand the test of time and endure for many years to come. The 1/60th or 1/125th of a second that the shutter stays open is one tiny moment in time, but if chosen correctly, can resonate for decades and generations. When I take photographs — particularly of great artists I respect and admire — I am deliberately trying to capture an image that can be used for years to come; because I know that this is the most important legacy I can leave as a music photographer.

This can sometimes be as straight-forward as a simple performance cliché, because clichés often exist for a reason. More often, however, it is a search for something unique and special — for me this is often an interstitial moment — somewhere between performance and non-performance; because this tends to suggest so much more than a simple performance cliché. Other times I like to play with technique to create movement and color to suggest mood, atmosphere and the passage of time.

What is the camera for Leon Morris?

The camera is a tool that helps me interact with the world of music I love. It makes me an active and contributing part of the industry I admire and enjoy. The camera is both part of me and separate from me. It can define who I am, but I try not to let the camera become more important than the performance, the event or the human interaction it is recording.

Essentially the camera is a device that records reflected light — nothing more, nothing less. It is the photographer that drives this device, making choices about how he or she uses the device and what he or she chooses to record.

I have mixed views about how the camera is used by myself and others. I don’t like what it does to distort the dynamics of human interactions. I don’t like the way I see many photographers use the camera — I generally find photographers aggressive and insensitive. That said, I am also very grateful to the camera: it has allowed me to develop and create my art, and it has provided me a passport to some extraordinarily powerful and inspirational performances, interactions and stories.

Miles Davis. Hammersmith Odeon, London, circa 1985 / photo by ©Leon Morris

People see only the final frame, the photographer get backstage. Please, tell about the most memorable shoot for you.

It is very true that people see only the final frame. Usually for every frame that the public gets to see, there are at least 20, and as many as 50, that do not get seen (and never will). This means the final selection is much more impressive than if people got to see all the discarded images. This is an important lesson for amateurs or early career professionals: what matters is the quality of the images you select, not the ones you reject. There are a few memorable images and shoots I could single out, but because I would select my image of Miles Davis from circa 1985 as my personal favorite, this is how I describe that particular shoot in the book.

Miles was sometimes criticized for his penchant to walk off stage or turn his back on the audience during live gigs, but this was, in my experience, to miss the point. A live Miles performance was not just about seeing Miles playing trumpet, but rather it was an invitation into the musical world of Miles Davis — and no one could give a more profoundly moving and insightful master class than the man himself — that is, if the listener was prepared to listen, really listen.

I was lucky enough to photograph Miles on two occasions — the first was at the Hammersmith Odeon in London, around 1985 — I think I was covering the concert for the New Musical Express at the time. Miles was in rare form, stylishly attired with a tassled jacket over a kind of up-market grey jump-suit and cowboy boots. A fedora hat and over-size sunglasses — two accessories guaranteed to make the life of a photographer difficult — completed the outfit. He prowled the stage like a lioness in charge of its cubs; restlessly moving on and off the stage; stepping forward to take solos and at one point stopping to pose for an audience members snap with a compact flash camera.

By chance, I met that audience member some years later in a flat in Kings Cross, London. She was a lifelong fan, absolutely devoted to Miles’ «Sketches of Spain» album. The photograph she took that night was a treasured memento — it wouldn’t have made the grade for magazine reproduction, but it reminded me just how powerful and evocative photographs can be, and how privileged photographers are to document the lives of major artists.

Tell us about your new project — «Homage: New Orleans».

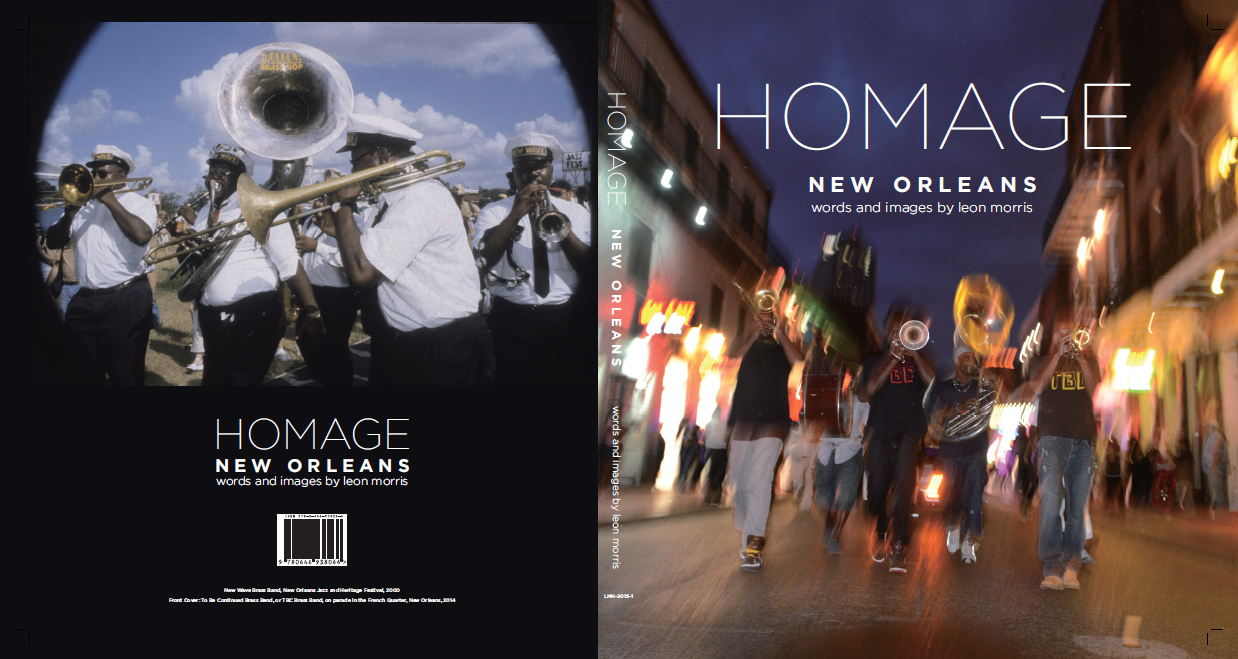

«Homage: New Orleans» is a collection of over 300 images and 60,000 words describing thirty years of music photography, the last twenty of which have been in New Orleans. Sub-titled, a personal journey in search of the roots and rock and pop, the book attempts to honor the importance of the city to contemporary music culture. I think it is important to remind all music fans of the role New Orleans has played in developing the musical genres we all know and love.

This is a city that has embedded itself in the words cultural sub-conscience. Largely unheralded, New Orleans has been responsible for the cultural alchemy (or gumbo) that gave birth to the two most important musical forms of the twentieth century — jazz and rock ‘n’ roll. This is not to say that the origins of both lie exclusively in New Orleans. That is not the case. But neither would have developed in the way it did without New Orleans.

It would, for example, be too long a bow (or too distorted a Stratocaster) to claim New Orleans as the sole or even the primary source of rock ‘n’ roll (Memphis may have something to say on the subject). However, rock ‘n’ roll and all its pop culture off-shoots could not have developed without the backbeat, a new Orleans innovation to accent the off-beats, the 2 and 4 beats in 4/4 time. This backbeat has become the underlying, all pervasive and dominant rhythm of the last half century.

Jim Dickinson, a Memphis veteran of the rock ‘n’ roll era, who passed away just a couple of months before I commenced writing this book in late 2009, challenged me back in 1996 to «imagine the world without rock ’n’ roll». That challenge could easily go further: to imagine a world without jazz, without rock ‘n’ roll and without New Orleans.

From a more personal point of view, the book describes my musical journey of discovery, with featured artists including New Orleans greats like Dr John, the Neville Brothers, Irma Thomas and Wynton Marsalis, and jazz, blues, soul, African and reggae legends like Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Nina Simone, Fela Kuti, Jimmy Cliff, Cab Calloway and James Brown.

I have been extremely fortunate to have pursued a career (or more accurately a series of careers) that has permitted me privileged access to so many wonderful artists and performances for over 30 years.

If there is one key motivation for my commitment to this «Homage» project, it is to share the joy and pleasure, and the occasional transcendent moment, that this privileged access has provided me. Music is a universal language. There is no people or culture anywhere on this planet that does not embrace music in one way or another, whether for recreation, pleasure, contemplation, solace, spiritual enlightenment, story-telling, inspiration, or movement and dance. Despite this universality, however, the musicians responsible for creating and developing this rich tapestry of our collective cultural heritage are by and large not afforded equal or due recognition. Indeed, many of the forms of music that I have come to love, and for which I am happy to evangelise, are essentially niche genres with very limited audiences.

The irony is that the huge and lucrative audiences associated with mainstream recognition would not exist without these niche genres, because they provide the foundations on which the development of all popular western music as we know it today has been built.

Excerpts from a new book by Leon Morris «Homage: New Orleans» provided by the author / © Leon Morris

text: Artem Kalnin

© Orloff Russian Magazine

Spy Boy Waddie, Golden Hunters with Hot 8 Brass Band, outside Tipitinas, 'Instruments a Coming'. New Orleans, 2003 / photo by ©Leon Morris

Leon Morris. «Homage: New Orleans» (cover)